You can download the COVID Alert exposure notification app in Canada now! It’s available on the iOS App Store as well as the Google Play Store.

See more details of how it works and what it looks like in my older post when I started using the beta:

You can download the COVID Alert exposure notification app in Canada now! It’s available on the iOS App Store as well as the Google Play Store.

See more details of how it works and what it looks like in my older post when I started using the beta:

[UPDATE – July 31]: The app is now publicly available. Go get it!

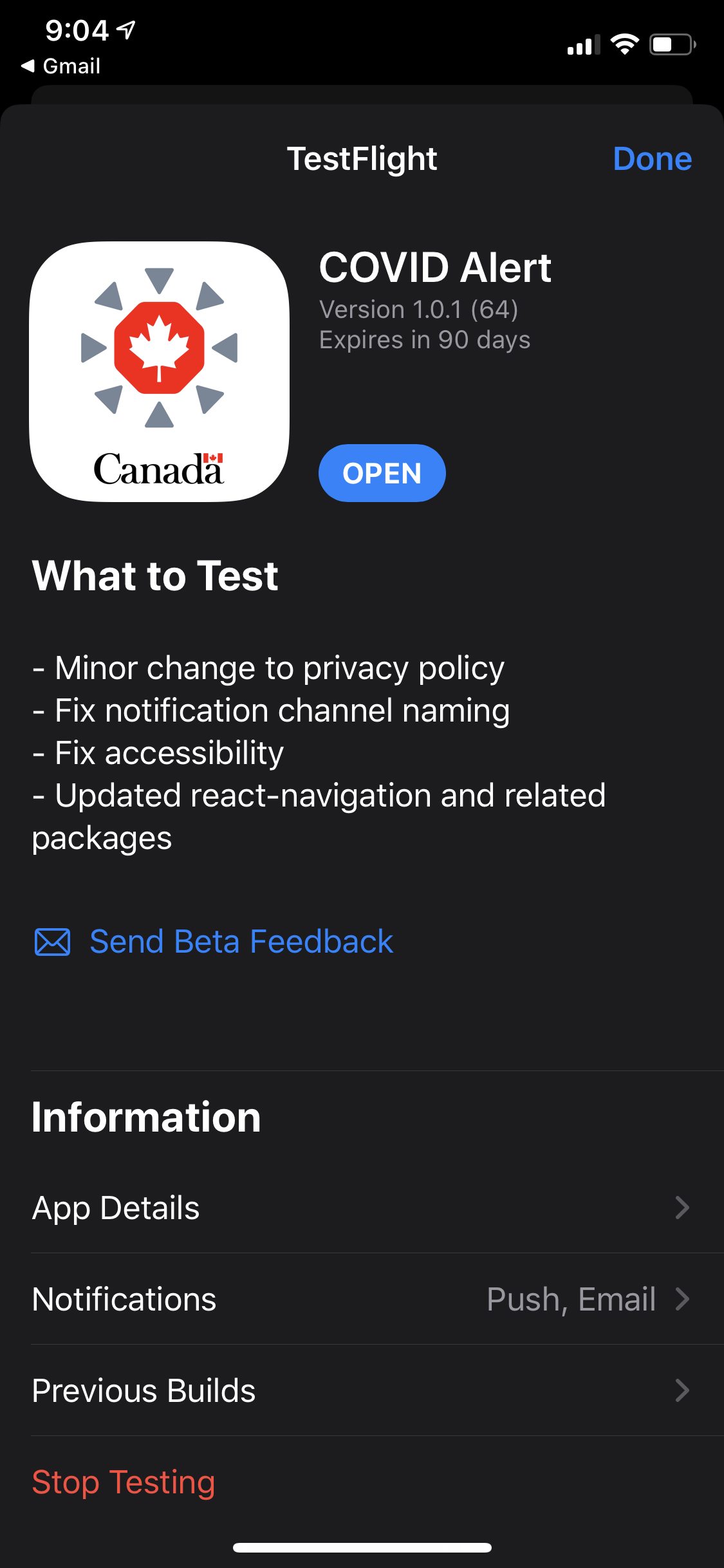

On Wednesday, Health Canada finally released a beta (test) version of the Canadian ‘COVID Alert’ exposure notification app.

I have been waiting for a couple of months to finally be able to get this set up once Apple and Google announced they would be building exposure notifications in to their operating systems, and it’s finally here (if you are willing to jump through some hoops and help test it out).

Let’s take a look!

When you first launch the app, you’re given a bunch of info right off the top. You’ll also have to accept exchanging exposure tokens with other phones, as well as receipt of exposure notifications, and then standard iOS app notifications as well. Here’s what the setup screens look like:

Once you’ve got everything activated, there’s not a whole lot to do besides look at the menus and edit your information.

I was informed via email they will be testing what an ‘exposure’ looks like in the app over the next 2-4 days, so if that happens, I will definitely share that information!

There’s not much to the app to be honest (which is a good thing), but there is a little more information to go over.

In the meantime, here’s some information provided under ‘How it works’:

These exposure notification apps (one per country, by rule) are meant to be for public health reasons only, so they’re very minimal, and outside of use in conjunction with your doctor, you won’t really notice it on your phone.

The only information the app collects and is able to use is a set of randomly generated ‘codes’ from the phones of others you interact with, and your phone sends out a similar set of ‘codes’ to people around you. No private information is stored or sent anywhere, like location or your personal details.

If you test positive, your doctor will give you a one-time use code which you enter in to the app, and this (if you choose to do it) will notify anybody else who has the app that you were nearby them and may have exposed them to the virus, because their phone has stored your ‘code’ from while you were near each other.

It’s a pretty incredible, secure system, and I’m really eager to have it see wide use in Canada and around the world, on Android and on iOS, over the coming months and possibly years.

When I hear more about the public release, I will post updates here!

This question is REALLY tough for me, mostly because it exposes some flaws in my understanding of how these systems are run. My understanding is the health care is currently administered on a provincial level, and most of my basic procedures and medical appointments are paid for by OHIP (the Ontario Health Insurance Plan). This is a public sector system, but private companies can handle all kinds of procedures which are then billed to OHIP.

I think the balance between private and public that we have in Ontario is pretty good, so I thought that things should pretty much stay the way they are (I certainly wouldn’t advocate for more private health care). I will say clearly that I’m also very ignorant of these things though, other then hearing about proposals for national drug coverage (Pharmacare), which I’m also fully in support of. This question/answer didn’t really help me at all, because it doesn’t give you any information about how much the federal government determines these things, and how much the private sector is actually involved in health care in Canada.

Summary: This is not the worst question, but with no context or information, I find it really hard to come to any conclusion other than to say I’m happy with how things are in Ontario, and we have some balance of private/public health care.

To be clear, before we begin, weight is just a number. For me, this is about how you feel. This may be less likely to work for you if you feel like you HAVE to lose weight, it’s much easier to keep doing something if it doesn’t require effort. I went from 250 pounds down to my current 195 while eating pretty much all the pizza I wanted, but the only time it ever felt like ‘work’ was when I had to convince myself my hunger was an illusion (which is usually is when we’re surrounded by readily available food).

Sorry for what sounds like a click bait headline, but this is an important lesson. What you eat, overall, is important for your health. Eating broccoli, salad, and less-processed food on a regular basis is really good for you. But if you’re concerned about your health or weight and want to change either, it doesn’t mean you have to stop eating the food you’re more likely to crave (like pizza).

I first started focusing on my overall health back in the summer of 2015. I had slowly put on about 40-50 pounds in the 2-3 years previous, and was considered obese (I weighed ~250 pounds all the way from summer 2014 to 2015, despite playing soccer that summer). No matter how active I was, my weight never went below 245.

It turns out, as I learned in the fall of 2015, the only thing that matters is being aware of how much you eat, and being able to control it (at least, for most people… medical conditions notwithstanding). Through a portion controlled diet, wherein I limited my intake of things like fries, pop, and other typical ‘unhealthy’ foods, I was able to hit 215 pounds by December of 2015, and by the summer of 2016 I was 190, lower than I’d been since middle school.

Keep in mind, while I did ‘limit’ my portions, and stop eating certain foods, I didn’t limit myself in any other way. I ate burgers, pizza, and snacked pretty much the whole time. But at a restaurant, I would get a soup or salad instead of fries, and if I indulged one day or for a weekend, I doubled down on my efforts the next few days after.

By doing this, I didn’t lose weight every day, but I did drop 2-3 pounds a week while I was biking, and continued to lose 1-2 pounds a week once it got too cold for that. I had a strategy that worked for me, and I felt better, looked healthier, and needed to buy a whole lot of new clothes.

Now, in 2017, I’m still biking to work every day I possibly can, and I’m ranging from 192-197 pounds depending on the day of the week (I’m not as strict on weekends). I have been weighing myself every day since July of 2015 (except on vacation), and I’ve still never felt better. I know exactly how much I should eat in a day to maintain my weight, and if I’m enjoying a good meal or snack, I let myself enjoy it!

So, this brings us all the way back to the title of this post. It really isn’t clickbait. I eat pizza around 6 times a week, and it isn’t the reason I weigh more on some days than others. I probably shouldn’t eat pizza as much as I am for my general health, but in terms of keeping my weight where I want, the type of food I eat has almost no bearing on that.

It’s all about being aware of how much you’re eating, and reasonable portions once you figure out how easy it is to overeat. For me, even more than calories in/calories out, it’s much more s matter of grams in/grams out. And it’s been working for over 2 years now.

I’ll have more on how I got to this point in future posts.

Why do I care so much that millions of people in another country, only a handful of whom I’ve ever met before, might lose their health care very soon?

I don’t know if I fully agree that riding a bicycle is for everybody, or that it’s the best possible treatment for any condition. However, I do know that, for me at least, riding a bike to and from work for the last several summers has given me more energy, revitalized my health and the way I feel, and helped me to lose 60 pounds since 2015.

While I was visiting family in Calgary for the last couple of weeks, I had the opportunity(ies) to drag my dad and cousin out for bike rides, something neither had really done this year after commuting by bicycle previously. Both were (hopefully) motivated by my eagerness to get out and enjoy the sunshine, and getting the first ride of the season in always helps make subsequent rides easier. Keeping that in mind, I hope both will continue biking when they can, because the benefits of incorporating cycling in to your everyday life are immense!

*The most striking statistic from this video is that in the Netherlands (and other Nordic countries), they consider every euro invested in bicycle infrastructure to be worth 8 euro in returns across the economy.

**As mentioned in the video, perhaps the *most* striking statistic should be the number of people killed in car crashes each year (33,000 in the US alone), but for some reason we accept this in society.

On July 1st, 2015, I weighed in at 248.5 lbs. Today, I average just under 195 lbs, and I feel better than I have in my entire life.

This isn’t a diet guide to compel you to buy something, hell, I’m not actually trying to sell or promote any product. What I do have for you is a set of principles, and things to keep in mind if you’re thinking about trying to lose weight.

When I set out to lose weight, I was over 250 pounds. I owned a WiFi-connected scale, I was already fairly active, and I had a deep-seated love of food. I was hoping that if I could stick to a diet, and exercise regularly, I might be able to get down to 210-220 lbs. I knew that would be a challenge, and that gaining the weight back would loom over my head.

I had been recording my weight with a scale that sent my measurements to a spreadsheet online since February of 2014, but those numbers alone didn’t help much for about 18 months. Then, in the summer of 2015, I started doing a few things that have fundamentally changed my life and made me WAY healthier.

First, I read this piece about how keeping a moving average of the last 10 days of weigh-ins could prove really helpful (and I made my own super-powered version of the spreadsheet; ask me about it!). Next, I started riding my bicycle to work. Third, and finally, I started taking Soylent to work and having that as my lunch.

By mid-September, after 2 months, I’d lost about 10 pounds, and found my appetite was starting to shrink. By the middle of October, 3 months in, I’d lost another 10 pounds, and was already more than halfway to my goal. This happened for a number of reasons, but the most important ones can be summarized like this:

Over the course of the last 13 months, I have been keeping meticulous records of what I weigh every day (vacations aside). I know that I’m not going to lose weight every single day, but I’m always surprised when I look at the stats of how the weight came off.

In the 407 days I’ve been tracking my weight, I lost weight on 242 of those days, which means I gained weight on 165 days. On the days I lost weight, I’ve lost a total of 241 pounds, and I gained back a total of 184 pounds on the other days. If you told me that the road to losing almost 60 pounds would include gaining over 180 pounds in a little over a year, I’d say you were crazy.

Such is the nature of weight loss. You won’t lose weight every day. When I started this little ‘experiment’, I was eating burgers and fries, and loving every minute of it, but I didn’t realize that I felt like garbage most of the time. Now, I feel vital and healthy almost all the time, and I’m much more likely to enjoy a delicious soup and salad at a restaurant.

My final piece of advice that I think is entirely common sense, but is hard to actually fully embrace, is that eating and food are rigged against you. Restaurants offer massive portions, and peer pressure and social situations can make it easy to eat way more than you want to do, or realize you are. Getting a salad isn’t “manly”, but I actually don’t enjoy more than a few french fries anymore, and I don’t miss them.

Making good choices feels weird, and sometimes, the ‘good’ choice is actually to just get something you’re really craving at a restaurant. That’s OK. Like I said, I gained 183 pounds in 165 days over the past year. That is a lot of indulgence.

It’s hard to ‘cheat’ at losing weight, because you have to actually eat healthier and form good habits if you want to make it a sustainable lifestyle. There’s no set of instructions anyone can write you to get you to a health or weight goal, and now, I don’t have one. I’m doing what feels good.

Moderation, and making changes you can enact permanently, are the best way to meet your health goals.

People who bike hate cars. People who drive hate bikes. You’re both wrong.

I personally take issue with anybody who doesn’t follow the rules of the road, or who (through apathy, or ignorance) puts others in danger.

The Ottawa Citizen has published a few pieces in the last couple of weeks about cycling, bike lanes, the driving/cycling dynamic, and a whole lot of other stuff pitting bikes against cars on the capital’s streets.

This kind of article is hurting a relationship that could be harmonious and mutually beneficial, if everybody could just agree to follow simple rules that already exist, and not presume they are special. Let me address a few points from the latest op-ed piece in the Citizen now:

I’ve never really understood just what it is that makes riding a bicycle so special. Sure, riding a bike is good exercise and an inexpensive way to get around, but that’s all it is.

This is such an incredibly shortsighted point. Isn’t this a very valuable and noteworthy goal, especially as cost of living rises in cities and obesity skyrockets around the world? Not to mention global climate change, to which any motor vehicles (including electric cars powered by coal) still contribute.

…[T]hey claim a right to ride on sidewalks as required and to ignore the laws that apply to bicycles. All while complaining about drivers and claiming that cyclists are subsidizing motorists.

Riding a vehicle on the sidewalk is illegal. You can get a fine for doing it, whether you’re in a car, or on a bike. Yes, people do it, but it’s because they don’t feel safe on streets. We live in a car-first culture, where many people are deterred from riding bikes when they hear almost daily about collisions between cars and bikes (which bikes always seem to lose). And like I said, bikes hate cars and cars hate bikes (in general). We all pay taxes and cars use roads much more than bikes do (more on that later).

…[C]ycling makes up about 2.7 per cent of the morning commute and two per cent over the whole day. As a means of practical transportation, it is close to irrelevant.

Considering how many people either have long commutes, poor health, or any number of other reasons (the feeling of danger notwithstanding) not to bike, this number would definitely be higher if cycling wasn’t an afterthought, and I’m sure we’d all be better for it.

You’d never know it from watching Ottawa’s cyclists, but a bicycle is classified as a vehicle under the Ontario Highway Traffic Act. That means cyclists must obey all traffic laws and have the same rights and responsibilities as drivers, but who hasn’t seen cyclists drive up on sidewalks, sail through stop signs, ride the wrong way on one-way streets and make unsignalled turns?

This one is almost too easy. Yes, a car and a bicycle are both vehicles. Cyclists need to obey traffic laws, and need to be responsible drivers and pay attention to their surroundings. However, on bike, on foot, and by car, I see cyclists and drivers up on sidewalks (check out #ottbike on Twitter), rolling through stop signs, driving the wrong way on one-way streets, and making turns and lane changes without signalling. Surprise, drivers do this just as often as cyclists.

I actually want to yell at cyclists who are in full gear, with racing bikes, when they roll through red lights to save a few seconds (both when I’m driving and when biking). Bad cyclists who refuse to wait their turn and follow the rules are just making the relationship between bikes and cars worse. We’re not all perfect, but we can be a lot better.

Without endorsing the practice, [Reevely] explains that cyclists make a habit of gliding through stop signs because bike routes off major roads are often on streets with stop signs every 50 feet. Actually stopping would take away all of a cyclist’s momentum. Similarly, cyclists ride on sidewalks because the city has refused to make major roads like Bank Street safe.

Clearly, these things happen, but who really thinks it’s safe to ride a bike on a sidewalk meant for pedestrians? One can easily imagine the sympathy a driver would get if he rolled through a series of stop signs, citing reluctance to wear out his brakes, or a desire to burn less fuel.

This practice of rolling through stop signs is not unique to bikes. Most drivers and cyclists don’t travel through stop signs without looking or slowing down (though I see the behaviour more often than I’d like in both).

However, the reason I think bikes and cars need to be treated a little differently when it comes to rolling through stop signs without coming to a full stop is as follows (spoiler – it’s all about momentum):

A bike and rider, weighing about 150-250 pounds together, moving at 5-10 kph, has a total momentum of 100-300 kg m/s. This means they can see if a car is coming and easily stop by lightly braking.

An average car, in 2010, weighed a little over 4,000 pounds. Even moving at only 2 kph, that’s still over 900 kg m/s, or more than 3 times as much momentum. Those of you who ride and bike will know that it’s much easier to stop a bike than it is a car over a short distance. In terms of safety for vehicles and pedestrians, a cyclist slowing right down as they approach a stop sign and looking both ways, is much better than the typical driving stop, which sees cars slow down and come to a nearly complete stop before heading off again. [editors note: if you come to a complete stop at every stop sign, you’re a beautiful snowflake, and an upstanding citizen, and also you’re probably lying to yourself.]

…[C]yclists are responsible for their own safety. Anticipating hazards when riding in urban traffic would seem to be a basic survival skill. A bicycle lane isn’t an autobahn for cyclists.

Totally agree with this point. Though I’m not sure you want to have to worry about your survival every time you hit the road, being aware of your surroundings, and the rules, are vital for drivers and cyclists. A bike lane doesn’t give you free rein to do whatever you please, but these lanes are also often disrespected by drivers too (see the bollards recently put up on Laurier on the bridge near City Hall). We all bear responsibility to get everybody home safe at the end of the day.

Of all the claims that are made about cycling, the idea that cyclists are subsidizing motorists is the most dubious. Cyclists use the roads, just like car drivers do. Unlike car drivers, they don’t pay licence fees and gas taxes to contribute to their upkeep. Everyone benefits from roads.

This is a fine point, but sort of misses the fact that bike-only infrastructure requires almost no upkeep, as the effect of bikes on roads is negligible compared to cars/trucks/semis. Add that to the fact that cyclists also drive on these roads at least occasionally, and likely pay for their construction and upkeep with taxes, and that argument loses a lot of its power.

Cyclists would get a lot more respect if they were willing to follow the rules of the road. This is not just because drivers like rules. It’s a safety issue. Unpredictable moves lead to accidents. Despite what some cyclists seem to think, drivers actually do not want to run them over.

Absolutely. Everybody needs to follow the rules of the road, and I have no doubt that cyclist unpredictability has a lot to do with accidents/injuries/collisions/fatalities where bikes are involved. Just like what happens when cars break laws or behave unpredictably. The only difference in this case is that when a car and bike collide, the driver of the car will never be hurt (physically) by the collision. This is where compassion comes in, and a little training, and learning the rules of the road, can go a long way towards bikes and cars sharing the road more safely.

Bikes are supposed to take about a meter from the curb, but are legally entitled to take a lane if they deem it necessary for safety or if the roadway is impeded in some way. If you’ve ever tried to bike in the one meter closest to a gutter, you will know it’s a VERY narrow swath of road, and one that is often full of potholes, construction equipment, drains, and other detritus that makes a ride perilous. Consider these facts as you commute by car.

Cyclists want to share the road too, and no cyclist wants to cause an accident (and on that last line from the quote above, I have heard drivers muttering or yelling about running over cyclists, and whether it’s in jest or not, I’m not laughing). We all want to get home safe at the end of the day.

Too many of our major streets are tough to drive on in a car, much less a bike. Fixing those roads, not more bike lanes, would be the best thing the city could do for cyclists and drivers.

I half agree with this. Some of our roads REALLY need a revamp, but I would argue the value of lanes for bicycles is pretty high in most places. Study after study shows the more car lanes you add to roads, the more traffic you get. More people end up buying cars, and you’re left with no less congestion. More space for cars isn’t helping anybody, whereas more space for bikes has great benefits for public safety, the environment, public health, noise pollution, traffic, and lots more.

The numbers are so huge they are not easily grasped, and so are perhaps best understood by a simple comparison: If U.S. roads were a war zone, they would be the most dangerous battlefield the American military has ever encountered.

I take the bus to work, and I absolutely love walking and biking. There are certain niche uses where a car is essential, but in an urban centre like Ottawa, many people can get around without relying on a car.

Having said that, just as many people, if not more, absolutely DEPEND on a car every day for transport to and from work and other social obligations. Most of this is because housing in big cities (Ottawa to some extent, Toronto and New York, for example, just take the example to astonishing extremes) is very expensive, so people choose to live where it’s cheaper, work in the urban centre, and commute for 30-60 minutes by car.

That thought is crazy to me. Even though I spend a ton of my life listening to podcasts, which are pretty perfect for car trips such as that, the thought of getting into a car every day to drive to the office is not something I think I’d enjoy that much.

Adding to that, we tend to think of car crashes as a tiny risk in our day to day lives, and it gets worse as those lives come to rely more and more on absolute certainty of normalcy. If our pizza is late, it’s free. If our Uber takes 10 minutes, we complain. When a bus breaks down (or doesn’t show up at all), we’re late for work.

But in a life (and society) where things are so safe (#firstworldproblems, anyone), the fact that any of us could die in such a quick, violent way on any given day is cause for alarm. We put car traffic above everything else in our transportation system, and yet it’s responsible for so many totally preventable deaths on our roads every day.

At some point, self-driving cars will take over, and crashes between two of those will be as unlikely as a plane crash is today. But for now, we’re stuck with an incredibly convenient transportation method where countless unknown cars around you are capable of completely changing, or ending, your life in an instant.

That’s scary, but it gives us something to strive for, and I think car culture as it exists now might be nearing its peak.

> The Absurd Primacy of the Automobile in American Life – The Atlantic

Canadians heeded the exhortation to reduce fat and reduced their fat intake to 31 per cent by 2004. But during this time, obesity rates spiked, which suggests that dietary fat is not a “primary contributing factor” in obesity, said the report.

I got healthy (and lost 45 pounds in the last 8 months) but not by focusing on eating healthier foods (like salads) at restaurants and at home. But my main focus was on the AMOUNT I ate, not on the types of foods as much. I didn’t count a single calorie, and though I started my diet exercising by biking to work every day, for the last few months I’ve only really been moderately active, but haven’t gained any weight back.

The demonization of fat (and subsequent need for people to eat lots of carbs at the grocery store, or restaurants, has meant that people have to eat a lot MORE food to feel full. Letting yourself eat fat, and trying to limit the amount of carbs you eat, is probably going to become increasingly important to the North American diet, whether these guidelines officially change or not.

> The Canada Food Guide is killing you: ‘The obesity epidemic… really began with our dietary guidelines’